ARM Assembly - Moving and Adding Registers

Two basic operations in the Assembly Language, as always, we need a way to move or copy values as well as doing arithmetic on them. Once we get add, subtract is also automatically done.

I learn about how the stack works at a basic overview level in low-level programming languages, and using that knowledge to recreate the echo utility in Assembly.

Published on Aug 4, 2025

Updated on Aug 4, 2025

Today, I want to write a simple program in Assembly, the echo command. It is very simple, it takes a string buffer from stdin and print it back out with no changes. There are a few concepts I hav e to research before being able to do this, since it involves working with devices (the input for stdin and stdout) and stack-based memory allocation.

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

char buf[1024] = {0};

fgets(buf, 1024, stdin);

fputs(buf, stdout);

return 0;

}A very simple C program, but there are actually a lot going on under the hood:

buf on the stack.stdin and write it to the buffer.The stack is different from the heap, is that it does not require a system call to allocate space on the stack. Traditionally, the program starts with the entire RAM as its stack, but in modern systems, I’m pretty sure the program starts with a set amount of bytes as the stack. When you try to write in a section that is not in the stack, the operating system would allocate and give you the stack space if needed.

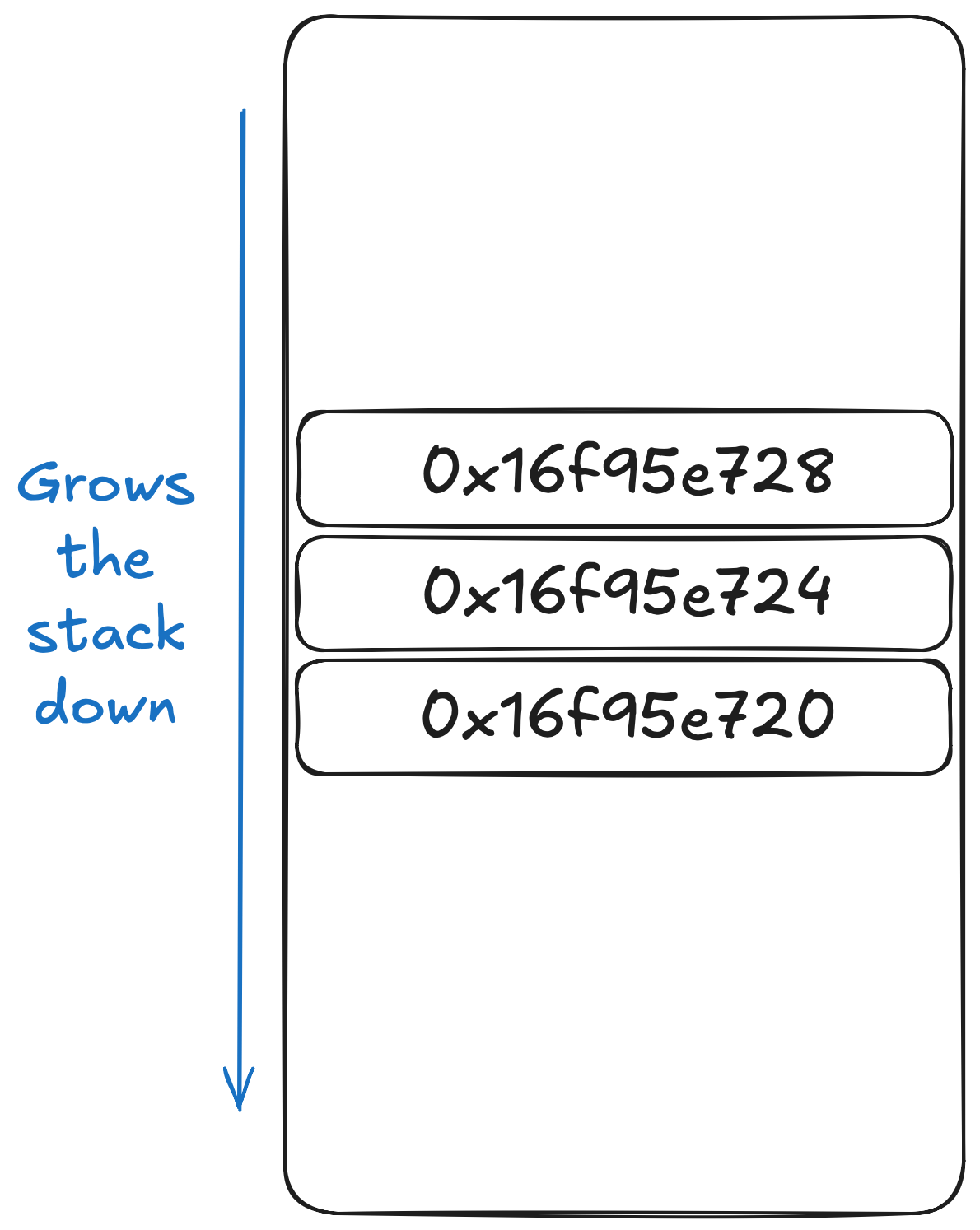

The stack is at its top when the program starts, and as you allocate, the stack grows down (meaning addresses are lower). You can check it out with a simple C program:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

int a;

int b;

int c;

printf("%p\n%p\n%p\n", &a, &b, &c);

return 0;

}Which gives the following output:

0x16f95e728

0x16f95e724

0x16f95e720You can see that the stack addresses go down by 4 bytes for each stack allocation we do. Although, some systems use ascending stack (stack that grows up), most modern systems like mine and yours use a descending stack (stack that grows down). I’m sure there is a reason to prefer one over the other, but that’s not my job.

In Assembly, you must know how much you need for the stack beforehand for each function. For example, the provided C program has 3 integers, meaning the stack was allocated for 12 bytes for that specific function, and after the function is done, it must return the stack back to the memory. This entire fiasco is called a function prelude. Specifically, the process of allocating the needed stack space is called a prologue and the process of collapsing the stack space back is called an epilogue.

The hard hitting question is here, how do we do stack manipulation. The answer is just to simply move the stack pointer (sp) downwards by subtracting how many bytes you need for it.

There’s a small problem with this. The idea of calling a function in Assembly is, saving the current function’s program counter to a register, mainly x30, then branch to that function (see more branching below).

The instructions we want to do for dealing with stack manipulation is compiled here:

| Instruction | Description |

|---|---|

sub sp, sp, bytes | Moves the stack pointer downwards by bytes bytes. This is an allocation. |

add sp, sp, bytes | Moves the stack pointer upwards by bytes bytes. This is a deallocation. |

stp x29, x30, [sp, #16]! | Allocates 16 bytes on the stack to store 2 doubleword registers frame pointer and link register. |

ldp x29, x30, [sp], 16 | Collapses the stack by 16 bytes after retrieving 2 doublewords and reassigns them back to x29 and x30. |

Are you clear yet? Let’s put out an example, for example, let’s say I want to allocate the stack for 3 integers, let’s do that!

sub sp, sp, 12Well, integers are 4 bytes, 3 of them are 12 bytes. Isn’t that simple enough? Yes, it is this simple, but remember that when you’re done, you have to collapse the stack by adding back however many bytes you allocated.

Well…, you’re probably asking wth stp and ldp instructions I mentioned is supposed to do then. It’s actually mostly used as function preludes. Here’s the problem without it:

A, which doesn’t use x30.B, setting x30 to a statement inside A to jump back from B.B calls C, then B sets the x30 to a statement inside B to jump back from C.C finishes and jumps back.B finishes, now where to jump back to? The memory pointing to A was overridden.This is why, as B calls C, it allocates a space on the stack to hold the FP and the LR correctly, then jump to C. Then when C jumps back to B correctly after C is done. Before B returns, it collapses the stack space and retrieves what the x30 was originally pointing at, which was A. Then when B returns, it jumps back to A correctly. This is the idea behind function preludes.

One of the most vital pieces of programming is the way to control the program flow. This is where control blocks come in, such as if, while, for, goto, etc. They essentially let you jump over blocks of code if a condition is satisfied, essentially breaking the conventional top-to-bottom sequential flow.

The main way to control the flow in Assembly is through branching. This will be used for all control statements you see in other languages. Even in a C program like before, we didn’t use any control statements, yet there are control flow blocks in the Assembly code (mainly, for zeroing out the buffer).

A branching instruction is in the form of b.condition where condition can be encoded with the following table’s values. The program state register, which you can’t read, but it decides IF your branching instruction will take place. This register contains four flags:

Z flag: the zero flag. This is set if the result is 0 or the comparison is equal. If the result is non-zero, this flag is cleared.N flag: the negative flag. This is set to the most significant bit on an operation. The most significant bit is always the sign bit, regardless of whether you use integers or floats, unless you treat them as unsigned integers.C flag: the carry flag. The carry flag is set if an addition operation overflows, or if a subtraction operation does not require a borrow. It’s also used in shifts where it holds the last bit that falls out.V flag: the overflow flag. Is set if a signed overflow occurred, if the result if greater than or equal to , or less than .| Condition | When will it branch? | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

b.eq | Z flag is set | Equality |

b.ne | Z flag is clear | Inequality |

b.cs or b.hs | C is set | Greater than or equal to (unsigned) |

b.cc or b.lo | C is clear | Lower than (unsigned) |

b.mi | N is set | Negative |

b.pl | N is clear | Positive or zero |

b.vs | V is set | Overflow |

b.vc | V is clear | No overflow |

b.hi | C set & Z clear | Greater than (unsigned) |

b.ls | C clear & Z set | Less than or equal to (unsigned) |

b.ge | N and V same | Greater than or equal to (signed) |

b.lt | N and V different | Less than (signed) |

b.gt | Z clear, N and V the same | Greater than (signed) |

b.le | Z set, N and V different | Less than or equal to (<=) |

b.al | Any | Always true |

You can implement loops by combining a comparison with a branching with condition.

mov w2, 1 // w2 = i

loop:

add w2, w2, 1 // w2 = w2 + 1

cmp w2, 10 // compare w2 with 10

b.le loop // if i <= 10 goto loopI’ll let you figure out how to deal with if, else.

Let’s look at the C program again:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

char buf[1024] = {0};

fgets(buf, 1024, stdin);

fputs(buf, stdout);

return 0;

}Okay, let’s tackle it step by step, first we do a function prelude (this is actually not necessary since our entire code does not call a subroutine, so that is entirely unnecessary, just keep it here to make it full):

stp x29, x30, [sp, -16]! // Allocate for x29 and x30

sub sp, sp, 1024 // Allocate stack space for char[1024]As you can see, we allocated 16 bytes to keep x29 and x30. Then we allocate 1024 bytes for char[1024] in the C code. Next, we have to initialize zeros into the buffer.

mov x0, 0

_main_zero_loop:

strb wzr, [sp, x0]

add x0, x0, 1

cmp x0, 1024

b.lt _main_zero_loopHere, we do a few steps:

x0 a starting value (0)wzr (the zero register), into the address indexed by sp[x0]. Essentially sp[x0] = 0.x0.x0 with 1024.Can you tell what C code this corresponds to? Next, we read from stdin to the zeroed out buffer with a syscall:

// Now we read from stdin

mov x0, 0 // 0 is stdin

mov x1, sp

mov x2, 1024

mov x16, 3 // read(fd, buf, count)

svc 0x80I’ll leave doing the printing to you as an exercise for the reader. For MacOS platforms, the system call for writing out is 4. The arguments that take in is the fd (file descriptor for writing out, stdout is 1), buf the write out, len how many bytes to write out.

Hint: after reading in, the length of the number of bytes read is saved in x0. Also depending on your Linux ABI, your syscall might be different. x64 Linux uses 1 for writing, ARM Linux uses 4 for writing (like Apple), but ARM64 Linux uses 64 for writing. You can check out https://arm64.syscall.sh/ for a list of syscalls based on your ABI. You can also check your ABI with the uname command.

~> uname -m

arm64My machine says arm64, therefore I have to use arm section on the syscall website. Wow that is confusing. If you’re on Linux and see aarch64 you use the arm64 set I think?

Anyway, here’s the proper way to get the syscall for MacOS machines: Link

The full code is available on my Github, thanks for reading!

Two basic operations in the Assembly Language, as always, we need a way to move or copy values as well as doing arithmetic on them. Once we get add, subtract is also automatically done.

Let's go over my first steps into the Assembly Language, using ARM64 syntax, and running on Apple Silicon.